Constructive Anger

How to deal with anger

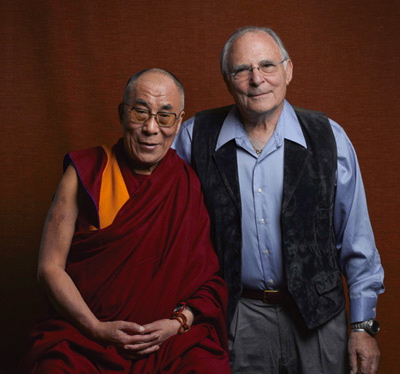

The following excerpt about constructive anger is taken from the book of dialogue between the Dalai Lama and myself, entitled Emotional Awareness (2009). Having just reread it, I found nothing to change; I still believe it raises the right question, makes a useful suggestion and offers a practice to learn it. It is only when life itself is threatened (our own or that of others) that we might need to focus on the actor rather than the action. Fortunately, that is a rare occurrence in the lives of most of us.

“Constructive Anger” Excerpt from Emotional Awareness, pp. 124-5

Ekman: I think [there is] a crucial issue for how people are educated about the way in which they can experience anger in a constructive fashion. You cannot get rid of anger, but you can learn how to use it in a way that is good for you. And the way that is good for you is not to hurt the other person. That almost always backfires. Unless you eliminate him or her, the person will come back and hurt you.

Dalai Lama: (Translated.) There is a famous story in the Buddhist texts about a Bodhisattva (in Mahayana Buddhism, this is known as a person who is able to reach nirvana but delays doing so out of compassion in order to save suffering beings*). This story seems to suggest an interesting take on the question, How can there be a compassion-motivated anger? The story is there is a Bodhisattva who is traveling on a boat. There is also a mass murderer on the boat and the Bodhisattva finds out that this person is going to kill all the other passengers. After failing to persuade the potential murderer to desist from what he is planning to do, he kills the mass murderer. The idea is that the Bodhisattva has full compassion for this potential murderer, but at the same time total disapproval of the act that he was about to commit. He has compassion for the mass murderer but anger against the act he is about to perform.

Ekman: In the 2000 conference, a group of us met one night to plan the research project to respond to your challenge, “Is this going to be just talk, good karma, or is something going to happen?” There were about six of us sitting around, beginning to plan. One of the participants kept raising obstacles: “You should not do this,” “you are reinventing the wheel,” and “why do you think you need to do this?” Mark Greenberg showed a beautiful example of constructive anger, because this person was putting an obstacle in our way. Mark said, “We really want to proceed, and if you want to participate, then we welcome you here. But if you do not want to participate, you should not stay in this meeting. You should let us do what we want to do.” He said it with strength. I asked him afterward, “Were you angry” and he said, “Yes.” But it was a very constructive anger. There was no element of trying to harm. He did not say, “Why do you think you know more than we know?” That would be harmful, right? Mark’s anger was totally focused on the action, removing the obstacle. Focusing anger on the objectionable action, not the actor, appears also in the writings of an emotion theorist, the late Richard Lazarus, who was a professor at the University of California at Berkeley, in exactly the same terms. What is needed, I think, is to give people practice in doing it. You could start with a situation in which anger was directed at the actor, and ask how you could instead direct the anger at the act. But that does not have as much life and vitality. We need exercises for developing this skill. When I anticipate that I will need to discuss an issue with my wife about which there might be some conflict, ahead of time I plan in my mind how I am going to deal with it. I actually go through a rehearsal in my mind: how I will direct my disagreement only at the act and be careful not to criticize her. I do not let her know that that is what I am doing. I have found it to be useful, and often successful, in finding a solution to our disagreement. You have to practice focusing on the act that is causing difficulty, not the actor; you cannot just think about it. This practice is based on a realization of our interdependence, but it is a practice, in my example, rehearsed in the mind.

* This definition has been provided to support reader understanding and was not verbally said by the Dalai Lama in this particular conversation.